The vision

“I want people to understand that vegan food isn’t just for a select few. It’s an inclusive eating style. Reaching beyond the vegan community is essential for creating a vegan-friendly world.”

— Azumi Yamanaka, a vegan activist in Tokyo

The spotlight

When you think of Japanese cuisine, your mind might go straight to sushi. Or pork ramen. Or, if you’re a little fancy, maybe Kobe beef. The country is famous for top-of-the-line meat and fresh fish. But did you know that, for 1,200 years, meat-eating was banned in the country? An emperor ended the ban In the late 1800s, as part of an effort to Westernize and open the island nation up to the world — against protests from Buddhist monks that eating meat amounted to “destroying the soul of the Japanese people.” The result: A rapid rise in consumption of meat, egg, and dairy products. Eating meat became a symbol of power and status, and eventually the cultural norm. Today, Japan ranks 11th in global beef consumption, and vegan options are difficult to find, especially outside of major city centers.

Two-hundred years ago, plant-based eating in Japan had a lot to do with religion and practicality. But today, some advocates are trying to renew the country’s interest in veganism — for climate and animal welfare concerns.

Grist fellow Sachi Kitajima Mulkey is Japanese and American, and spent years living in Kyoto where her family is. “When you’re an American living in Japan, your friends visit all the time. They’re so stoked to have a free place to stay,” she said, adding that many of her American friends were vegetarian or vegan. “And I just remember how hard it was,” she said. Meat, eggs, and dairy were difficult to avoid, not to mention the dashi, or fish broth, that forms the base of many dishes.

But then, something shifted. Around five years ago, she started noticing vegan products at the stores and restaurants she went to. “Almond milk was suddenly available, when it wasn’t before,” she recalled. Earlier this month, she teamed up with Grist’s Joseph Winters to write a feature on the rise of veganism in Japan.

Interestingly, the push to include more vegan options in restaurants and supermarkets seems to be fueled in part — again — by the country’s desire to cater to outsiders. “A lot of the new vegan initiatives are driven by an increase in tourism and trying to accommodate tourists,” Winters said. For instance, in the lead-up to the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo (which wound up being held in the summer of 2021), the government developed a set of guidelines and certification marks to help restaurants offer more vegan options for visitors, and even offered subsidies for them.

But the push to increase plant-based options is also a part of meeting national and local climate goals — Japan has pledged to halve emissions by 2030. In the city of Kyoto, which has its own aggressive emissions targets, plant-based eating is part of the plan to get there.

Still, barriers exist for Japanese residents who want to go vegan. Some mirror the barriers that many face in the U.S. — a lack of accessible options, and a stigma that meat-free diets are not nutritious — but some are also unique to Japan’s customs. “It is a culture where bucking the norm is really looked down upon,” Mulkey said. “It’s very difficult to feel like you’re asking for any kind of special accommodations. It’s all about humility and the group and fitting in.”

Mulkey even experienced this herself when she was home visiting family and reporting the story. She tried to eat vegan as much as she could, but was concerned about offending her loved ones by turning down meat, or inconveniencing them by dragging them to yet another vegan restaurant.

Winters joked that this is often what it’s like traveling as a vegan. “It just becomes a food travel experience,” he said. “You have your list of all of the sights, and it’s just vegan restaurants — and then like, ‘OK, I guess we’ll go see the Sistine Chapel or whatever.’”

As far as the impact of the story, Winters hopes that reporting on veganism and the way it’s showing up in different parts of the world can help make the idea more accessible for people. And Mulkey noted that she was particularly excited to frame the story with a Japanese audience in mind (the piece was co-published with The Japan Times).

“It’s exciting to see a culture that is so slow to change kind of move quite quickly on this, actually,” she said. “It is nice to think that, in a moment where the country does want to open itself up for more travel and have people visit, it can accommodate people more.”

In the excerpt below, Mulkey and Winters delve into the history of Japan’s relationship with meat, and also what vegan advocates and chefs are cooking up — and working against — today. Check out the full piece on the Grist site, here.

— Claire Elise Thompson

![]()

In meat- and fish-loving Japan, veganism is making a comeback (Excerpt)

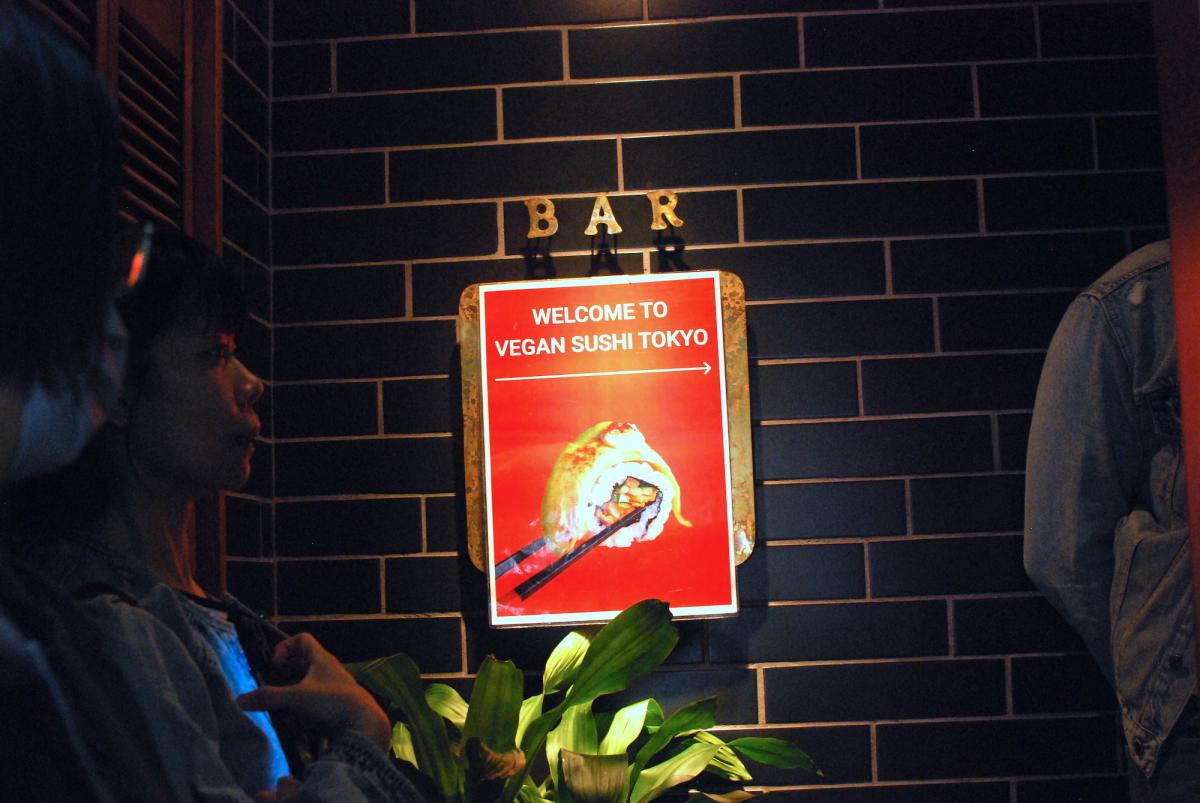

All is quiet at 10:30 a.m. on a Thursday in Shibuya, Tokyo’s famous commercial district. In an alleyway just steps from one of the busiest train stations in the world, a short line of tourists huddles outside of a bar. Finally, half an hour later, the door cracks open and, greeted with a soft irasshaimase, or “welcome,” the parties shuffle in to sample one of the rarest dishes in Japan: faux-fish sushi.

“Nowadays, there are many vegan ‘meat’ products,” says Kazue Maeda, one of the four founding employees of the restaurant, Vegan Sushi Tokyo. “But I’m Japanese. What I really used to love is sushi and salmon.”

Her restaurant attempts to fill a relatively unclaimed niche in the local food scene. Even in Tokyo, where much of the country’s vegan population lives, plant-based versions of traditional Japanese food remain challenging to find — most vegan options are yōshoku, a popular cuisine that puts a Japanese twist on Western dishes like hamburgers. Vegan Sushi Tokyo is open only for lunch: Although rave reviews keep pouring in from customers, the small business still doesn’t have a storefront of its own and rents out the interior of a bar by day. It serves 10-piece nigiri lunch sets, which include a plant-based Japanese-style “egg,” “shrimp” tempura, and beads made out of seaweed that look nearly indistinguishable from salmon roe.

For all its differences from the United States, Japan’s culinary culture takes after America’s in a key way: It’s difficult to avoid meat and dairy. Of course, soybean products like tofu are the star of many dishes. But beef, pork, chicken, eggs, or dairy also feature in nearly everything, from ramen to okonomiyaki, a savory cabbage and pork pancake. And then there’s the fish — served raw in sushi and sashimi, grilled as fillets, fried in tempura, shaved as a garnish, and present in nearly all other dishes as dashi, a savory broth made of dried tuna flakes and kelp.

Maeda became a vegan six years ago, due to her growing concern over environmental and animal rights issues. It’s a familiar origin story for those who have come to defy the typical Japanese diet by giving up animal products. “In terms of the vegan movement, I think we’re maybe behind other countries. The number of vegans is very small,” Maeda says. “But there are more and more vegetarian and vegan restaurants in Tokyo, I think because of tourists — especially from countries with many vegetarian people.”

Outside large cities like Tokyo, Osaka, and Kyoto, vegan options quickly vanish. In a culture that prizes convention and scrupulous attention to detail, individual accommodations — like vegan menu substitutions — are often frowned upon. And as in many other countries, vegan options are sometimes stigmatized as less nutritious.

But recently, things have been changing. The anticipation of a tourism boom for the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo pushed the Japanese government to encourage new vegan businesses and menu options in major cities. And in the years since, restaurants like Maeda’s have sprung up, offering novel adaptations of traditional dishes. Under pressure from Japan’s pledge to nearly halve its carbon emissions by 2030, the government has also begun collaborating with vegan activists and advocates and awarding grants to alternative protein start-ups. Though challenges remain, it’s gotten easier and easier to go vegan in Japan over the last decade.

“Climate issues and animal issues are growing,” Maeda said. “For me, I can’t imagine going back to eating meat again.”

The first guests of the day line up outside the door of Vegan Sushi Tokyo in Shibuya. Sachi Kitajima Mulkey / Grist

Convincing people to eat less meat is key to reaching international climate goals. Up to 20 percent of planet-warming greenhouse gases emitted annually come from animal agriculture alone — all the cows, pigs, lambs, chickens, and other animals (not including fish) that people raise for meat, milk, eggs, and the like. According to one study from the University of Oxford that looked at the diets of over 55,000 people, vegans — defined as those who eschew all animal products — create 75 percent less climate pollution through their food choices than those who eat a meat-heavy diet.

For most of the last two millennia, the Japanese diet was a model of climate-friendly eating due to Buddhist and Shinto objections to meat and dairy consumption — although fish has long been a staple. Beginning in 675 A.D., meat-eating was banned by official imperial decree.

The ban set the stage for the flourishing of shōjin ryōri, a traditional cuisine that arrived in the sixth century along with Buddhism and aligns with the religion’s prohibition against killing animals. In the 13th century, the cuisine developed into a spiritual movement focused on simplicity and balance between one’s mind and body. “‘Shōjin ryōri’ literally means ‘food for spiritual practice,’” one Japanese studies professor told the BBC.

A typical shōjin ryōri set meal is vegan, highlights seasonal produce, and is designed around sets of five — five colors, five flavors, and five cooking methods. While it can still commonly be found in the dining halls of Buddhist temples, modern chefs have taken shōjin ryōri into the mainstream, including in Michelin-starred restaurants, where they emphasize the concept’s focus on harmony with nature by using local ingredients and minimizing waste.

It wasn’t until 1872 that Emperor Meiji lifted the meat-eating ban, seeking to usher in an era of Westernization. Meat consumption grew quickly as domestic beef production boomed, and animal products became a symbol of power and status. As reports spread that Emperor Meiji drank milk twice a day, dairy consumption became more popular, too.

Today, Japan ranks 11th in beef consumption globally, and its per capita milk consumption is 68 percent higher than that of the average East Asian country. Japanese people buy eight times more meat than they did in the 1960s, and in 2007, families began eating it more than fish. (Japanese people still only eat half as much meat, not including seafood, as Americans.)

But interest in plant-based foods appears to be growing, as it is in Western countries. Japan’s market for plant-based foods tripled between 2015 and 2020, and the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries expects it to double again by 2030. These shifts have taken place as the Japanese population at large has expressed a readiness to shift toward plant-based products for health, animal welfare, and climate-related reasons, according to a 2022 analysis in the Journal of Agricultural Management.

Although no official government statistic exists, a 2021 survey found that 2.2 percent of Japanese people identify as vegan — a potentially higher percentage than in the United States, where estimates range from 1 to 4 percent.

But even though vegan restaurants have been on the upswing since 2017, Japanese vegans seem to have fewer options than their American counterparts. According to HappyCow, a popular directory of vegan and vegetarian restaurant options, Japan has fewer than six vegetarian restaurants per 1 million people in Japan, more than a fifth of them in Tokyo. By comparison, there are nine vegetarian restaurants per 1 million people in the U.S.

“Even many chefs still don’t know what vegan is, they don’t know the concept,” said Azumi Yamanaka, a vegan activist in Tokyo. She met with a reporter from Grist for a late lunch at Brown Rice, a sleek vegan restaurant with an organic, health-focused menu near Harajuku, the country’s famous fashion capital. For her meal, she ordered the weekly teishoku special, which came with a selection of small seasonal vegetable dishes, rice, and miso soup. “They don’t realize that adding a small piece of bacon or fish is still meat. I still have to explain it,” she said, while picking at a slice of roasted lotus root with her chopsticks.

When Yamanaka became vegan 16 years ago, she said, most people in Japan hadn’t even heard of the term “vegan.” Pronounced bi-gan, it joins a lexicon of Western loan words that have been integrated into the language with Japanese phonetics, such as ko-hii (coffee) or chi-zu (cheese). But in recent years, she said, being vegan has become a somewhat fashionable subculture — judging from social media trends and an upswing in photogenic vegan cafes, which she said get more young people interested in becoming vegan, too.

— Sachi Kitajima Mulkey and Joseph Winters

More exposure

- Read: about the growth of veganism in another meat- and dairy-loving country: the U.K. (The Guardian)

- Read: a story about the tradition of eating wasps in Kushihara, a Japanese mountain village (Splendid Table)

- Read: a diary-style article from a writer who spent a week sampling faux-fish products (Grist)

- Read: a guide to the best vegan sushi spots in Tokyo (Tokyo Weekender)

A parting shot

While Mulkey was in Japan visiting her family, she got to sample a number of vegan treats in Kyoto. Here’s a shot of soy milk-based ramen at Mumokuteki, a natural lifestyle store with a vegan cafe. Mulkey described the ramen as “so, so yum.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Veganism has deep roots in Japan’s history. It’s beginning to resurface. on Feb 5, 2025.

In this excerpt, Grist’s Sachi Kitajima Mulkey and Joseph Winters explore how vegan diets are gaining a foothold in Japan — and the cultural barriers that still stand in the way. Grist