This coverage is made possible through a partnership between Grist and WBEZ, a public radio station serving the Chicago metropolitan region.

Four years ago, Democratic Illinois Governor JB Pritzker signed the Climate Equitable Jobs Act, an ambitious suite of overlapping goals and deadlines to put Illinois on track to overhaul its economy by 2030: decarbonizing the power sector, propping up electric vehicles, and fast-tracking a clean energy workforce.

Now, with five years left until several deadlines are due — and a presidential administration that doesn’t believe in climate change — the clock is ticking. As climate action shifts more to the local level, states have to figure out both how to fill the void left by the federal government and how to hit targets that now seem likely out of reach.

Illinois isn’t the only state to set hard-to-hit goals and come up short. States such as California, New York, and Oregon are playing a similar game of catch-up. That doesn’t come as a surprise to Jackson Morris of the national nonprofit Natural Resources Defense Council, or NRDC, who added that it shouldn’t be a death knell for climate initiatives either.

“[The] momentum at the state level, particularly now with what’s going on in Washington, is really where the action is,” said Morris. “ We want to push as hard as we can to meet as many of those targets as we can, even if they happen a year or two years after — the important thing is that we’re on that long term trajectory.”

Illinois came face-to-face with one of its renewable energy targets this year and came up short, according to John Delurey, with the national advocacy organization Vote Solar.

Before the Climate Equitable Jobs Act, known as CEJA, the state had committed to relying on renewable sources for a quarter of its energy by 2025, Delurey said. But as of 2023, renewable energy only made up about 13.5 percent of electricity generation in Illinois. That figure needs to more than double over five years to catch up with CEJA’s impending deadlines.

CEJA increased Illinois’ renewable portfolio standard — a policy that requires that a certain share of the energy sold by electric utilities comes from renewable sources — to 40 percent clean energy by 2030, to 50 percent clean energy by 2040, and to 100 percent by 2050.

“We have a long journey ahead and a short time to get there,” Delurey said. “But I don’t know that it’s a foregone conclusion that we will miss our 2030 CEJA goals.”

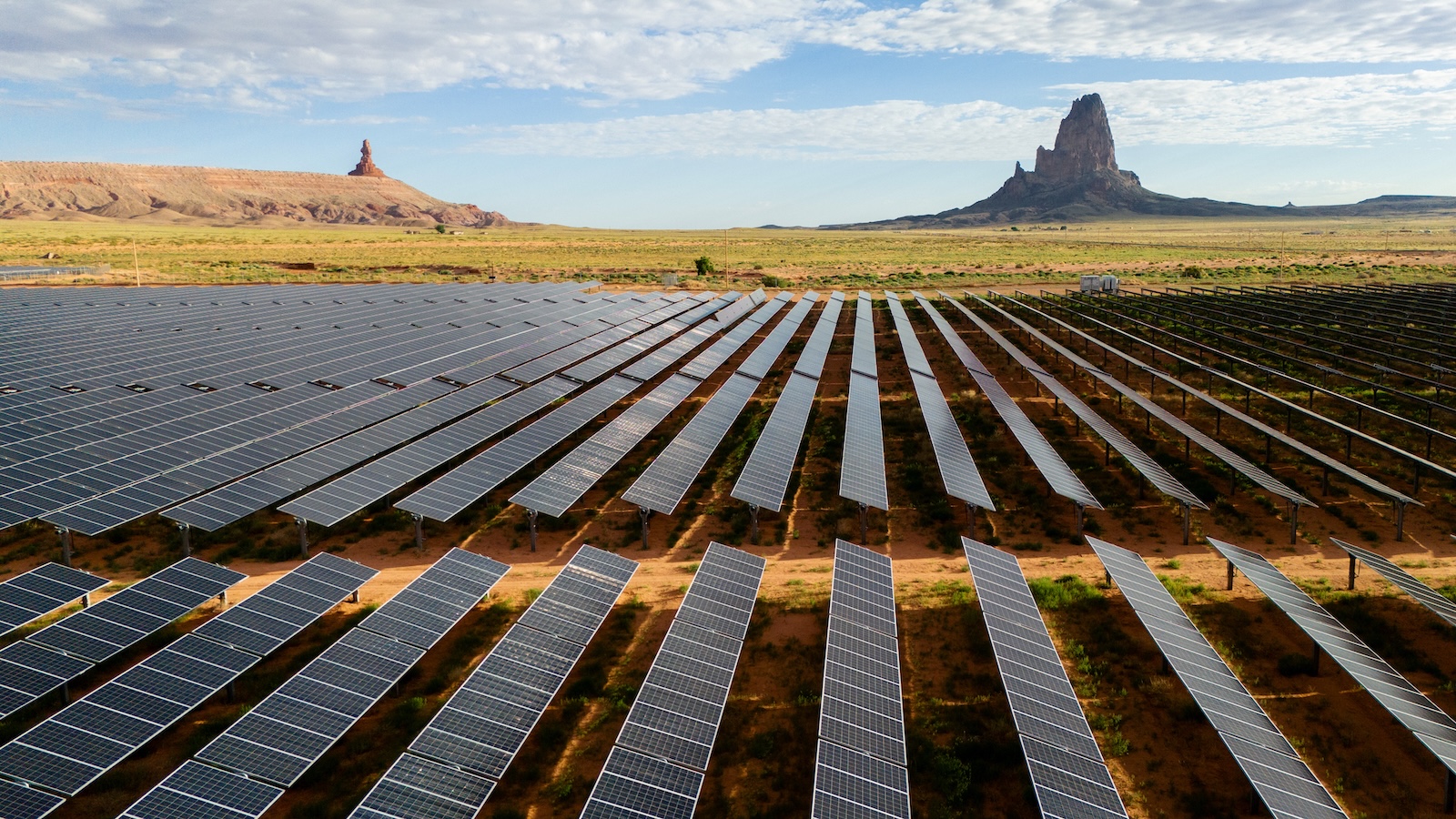

In Illinois and across the country, the installation of wind projects has slowed substantially compared to solar, which has soared, particularly with the help of tax credits from former president Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act. That’s increasingly a problem in Illinois, where over 90 percent of the state’s renewable generation comes from wind.

Wind has tapered off locally, according to Delurey, due to issues with increased local opposition around where renewables can be installed.

“At the peak, about 15 counties in the windiest part of Illinois had effectively banned wind projects,” he said. That was before Illinois passed a 2023 bill to limit what local governments could do to restrict wind and solar.

A recent report from the nonprofit Natural Resources Defense Council found that regional grid operators are moving too slowly to keep pace with massive expansion of renewables. As a result, renewable energy projects have been stuck on a waiting list for years before they come online.

Still, Brian Granahan, director of the Illinois Power Agency, which brokers electricity between customers and utilities, said the state has made significant progress toward its 2030 target of 40 percent clean energy.

“In terms of the contracts that have been awarded through our programs and procurements, we’re at 19 percent right now,” Granahan said. That figure, however, includes clean energy projects active today and those that are still under development.

Granahan said that Illinois is about halfway to its 2030 deadline.

“The question is, Over the remaining five years, can we award enough contracts to make up the remaining 20 percent to ensure that we’re making up the other half,” he said.

It’s not just renewable energy targets that are lagging. So are plans for EV and clean energy workforce training.

The state’s landmark climate legislation set a target of 1 million electric vehicles on the road by 2030. To date, only about 100,000 EVs have been added in Illinois since Pritzker signed CEJA.

The state isn’t doing enough to close that gap, according to Brian Urbaszewski, director of environmental health programs at Respiratory Health Association, a Chicago-based public health nonprofit.

“There’s not a lot of detail in terms of year-by-year goals,” he said. “It was just a big goal that we’re going to reach by this date.”

The centerpiece of the plan was a $4,000 rebate for Illinois customers with the purchase of a new or used EV, which could be stacked on existing federal tax credits.

However, funding for the rebate program has been insufficient to meet demand each year since launch. The program’s funding fluctuates, depending on how much Illinois lawmakers set aside for it. Funding for fiscal year 2025 is down to $14 million from a one-time high of $20 million in 2023. This year’s rebate program will only provide payouts for approximately 3,500 EV purchases. That’s not enough, Urbaszewski says

Today, more than 7 million passenger vehicles run in Illinois, the vast majority gas-powered. That means that even if the state adds a further 900,000 EVs on its roads by 2030, the result would still be relatively “modest,” according to Urbaszewski, as only a sliver of total passenger vehicles would be zero-emission.

The Illinois Environmental Protection Agency declined a request for an interview and did not return a request for comment.

Still, there is a glimmer of success.

After a yearslong wait, the state is finally delivering on its promise to build out workforce training for clean jobs. Illinois has committed to $80 million annually to rapidly expand training and certification programs, with an emphasis on Black and Latino communities most affected by pollution from fossil fuels.

As part of that effort, the state established 16 community-run workforce hubs across the state. Their purpose is to provide entry-level training relating to green-economy careers. To date, there’s already been 15 graduates, and more than a hundred students are currently enrolled.

It took time to build up the capacity to get these programs operational, according to Francisco Lopez Zavala, a policy expert with The Illinois Environmental Council, an umbrella organization that advances environmental policy statewide.

“We’re trying to ensure it is done in a way that’s equitable to our communities across the state, and is done right by our communities,” said Lopez Zavala. “It takes time to do right by them.”

As the 2030 deadlines approach, it’s becoming clear that states like Illinois may miss the mark. From the NRDC’s Jackson Morris’ perspective, that’s not necessarily a failure.

“We always knew that the path to a net zero economy by 2050 was not going to be linear,” said Morris. “There are going to be years where you make more progress and years where you flatline. It’s going to be lumpy.”

Between President Donald Trump’s recent withdrawal of the United States from the 2015 Paris Agreement to cut greenhouse gas emissions and a slew of executive orders to stall renewables, state-led decarbonization efforts — even if they are behind schedule — may soon be the only large-scale greenhouse gas-slashing strategies left in the United States.

“I’d rather see states take shots from half-court and try to make them,” he said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The odds are Illinois won’t hit its 2030 climate goals on Feb 7, 2025.

From renewables to EVs to workforce training, the state’s journey toward decarbonization has “a long way to go and a short time to get there.” Economics, Energy, Politics, Transportation Grist