Seeds are special for Nina Raj, a docent at the Eaton Canyon Nature Center and the founder of the Altadena Seed Library in Southern California. So when Raj and her partner fled from the Eaton Fire on January 7, her first thought wasn’t to pack clothes or important paperwork. Instead, she grabbed Matilija poppy, California buckeye, sage, and buckwheat seeds from her greenhouse — part of a seed bank she’d started to gather alongside a team of volunteers.

Raj’s home escaped the fire unscathed. But the rest of Altadena, known as a thriving hub for multigenerational Black and Latino families, wasn’t as lucky. The Eaton Fire burned at least 9,400 structures and killed 17 people there; up the coast, the Palisades fire destroyed more than 6,800 structures and killed 12. Both blazes were fueled by bone-dry conditions and hurricane-force winds. Climate change helped set the stage for the extra-dry fuels and nonexistent rainfall: A study published last month found that such hot and dry conditions are about 35 percent more likely due to climate change.

Recovery is still nascent; people began reentering burned neighborhoods in late January. But Altadena residents say that when the time comes, they’re ready to thoughtfully regrow their community, once full of lush trees, native plant landscaping, and backyard vegetable gardens.

The Altadena Seed Library, a network of seed exchange boxes, is leading the charge. Raj’s project began in 2021, with several little seed libraries stationed around the community. Seed libraries mimic regular libraries, but instead of books, people check out (and use) envelopes of seeds for free. Now, Raj and other volunteers are working on a game plan for regrowing the lawns, gardens, and urban green spaces that combat shade inequity and increase food sovereignty in their neighborhood — and looking to learn from other communities that have also seen their landscapes drastically altered by destructive wildfires.

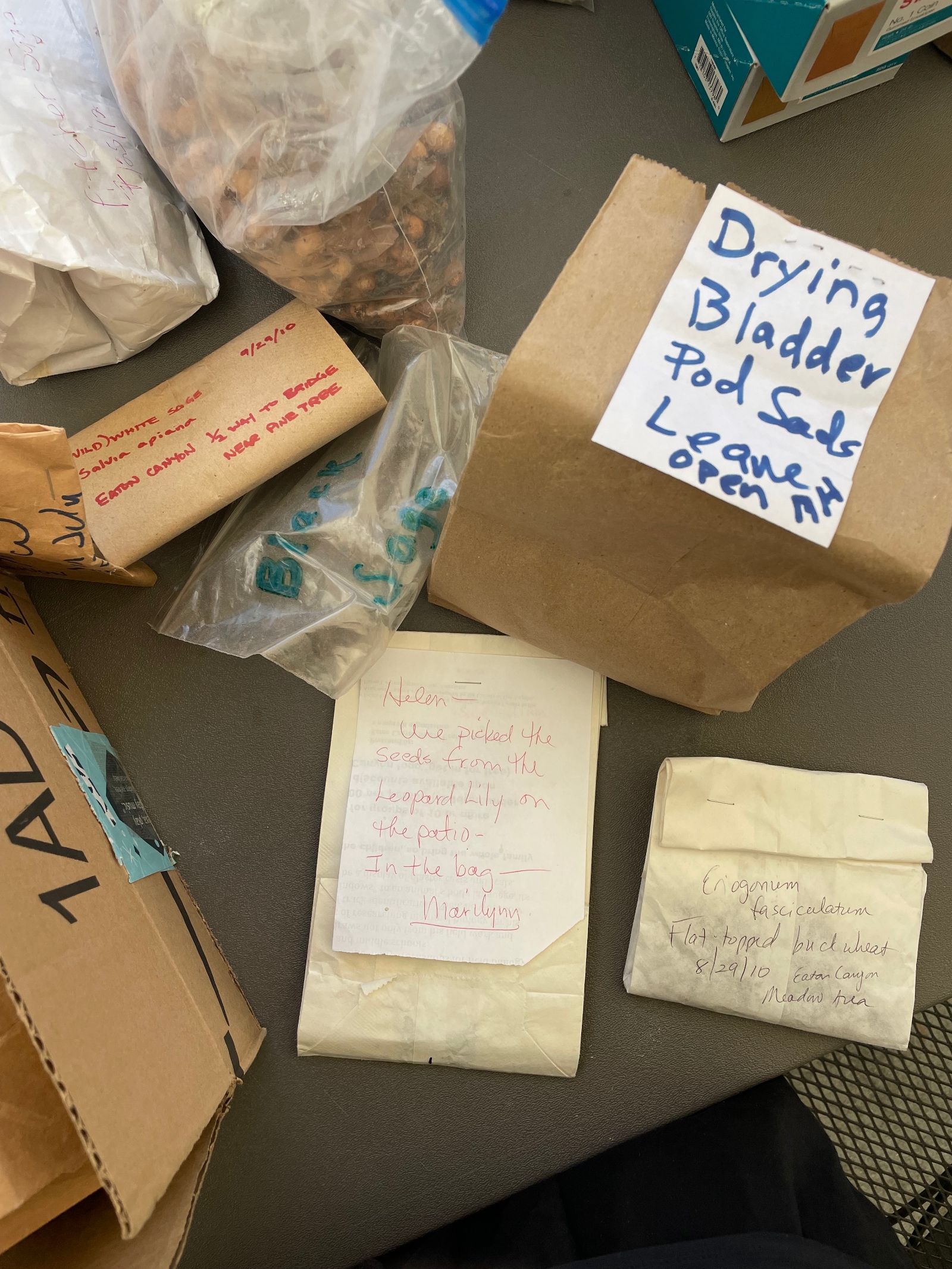

Donated seeds and tools are pouring in from locals and places around the country, as well as compost, pots, trees, and personal protective equipment for people cleaning up the hazardous waste leftover from burned homes and melted cars. “We’ve had a pretty overwhelming response,” Raj said. “People have been so, so generous.” Individual volunteers and organizations like Club Gay Gardens, a nonprofit in nearby Glendale, are helping sort the donated seeds.

Clockwise from top left: Nina Raj, founder of the Altadena Seed Library; a sampling of seeds being sorted for the library last year; Raj started the seed library in 2021 to expand access to shade and green spaces, increase food sovereignty, connect neighbors, and restore local ecosystems. Courtesy of Nina Raj / Altadena Seed Library

Wildfires that spill over into neighborhoods, known as wildland-urban interface fires, burn cars and homes full of dangerous chemicals, from paint thinner and lithium-ion car batteries to fertilizer. Breathing in asbestos, lead, and other heavy metals is one of the most pressing concerns as residents return to ash-choked neighborhoods. Landscaping tends to happen at the very end of the rebuilding process, when homes are reconstructed and heavy machinery work is complete.

When the time comes, Raj and other community leaders will need the proper permits to plant in the public spaces beyond private yards and gardens. But before residents can replant anything, they must consider testing the soil for toxins and remediating it accordingly. This can be expensive — about $100 to test one soil sample for heavy metals.

In the meantime, Altadena Seed Library is specifically requesting seed donations for native plants that are known to help remediate the soil by soaking up toxins, including California buckwheat, telegraph weed, saltbush, mule fat, and Bush sunflower. “It’s good to figure out which contaminants you’re dealing with, and then look into what plants will help you,” said Maggie Smart-McCabe, the co-leader of Club Gay Gardens. “If you can, native plants are great, because then it helps with rebuilding the habitat that’s been lost, too.”

Eventually regrowing Altadena’s urban greenspaces and canopy could mean confronting how previously introduced plants — like ornamental grasses, eucalyptus, and palm trees — helped spread flames, and not replanting them. “These palms that are so common in Southern California have these dead fronds at the bottom of them,” said Alexandra Syphard, a senior research scientist at the Conservation Biology Institute. “That’s the opposite of what you would want to do to have a fire-resilient landscape.” The Los Angeles County Fire Department calls palms a “known hazard” and discourages planting them in wildfire-prone areas.

Plants that hold more moisture, like oak trees, are likely more resilient to wildfire embers than other plants. Many conifers, including cedars and pines, survived the Los Angeles fires, as did some native oaks. “People have a chance now to create their landscapes, their gardens, their properties from scratch, and they have an opportunity to create something that is beautiful and also safe,” Syphard said.

Replanting efforts in Paradise, California, where the Camp Fire killed 85 people in 2018, and Lahaina, Hawai‘i, where a wildfire killed 102 people in 2023, offer inspiration as to what responsible reseeding can look like post-fire. Wildfire survivors from up and down the West Coast have already reached out to Raj, offering to help Altadena. “It’s so unfortunate to be bonded in that way,” Raj said. “It also feels really beautiful that those connections can grow out of something so tragic.”

The Federal Emergency Management Agency helped test for soil toxicity in Paradise, eventually scraping the contaminated top layers away. But replanting efforts were left to residents. “None of this would have happened if it weren’t for these community groups that all came together,” said Jennifer Peterson, a Paradise local who saw her house, plus a seed library and two community gardens she worked on, destroyed.

Peterson and other community members worked hard to safely reestablish old food sources. In 2020, several groups and 300 volunteers joined forces to rebuild — in one day — a nonprofit arts and culture center whose public gardens provide compost, seeds, and produce for free. Grant money allowed organizations like the Butte County Local Food Network to prepare 150 garden boxes and deliver them to people’s homes, complete with new soil and plants.

Courtesy of Jennifer Peterson

Being part of efforts to regrow people’s food — and her front yard, which now teems with native wildflowers whose seeds survived the fire — has helped Peterson heal. “It was kind of like therapy for everybody,” she said.

In Lahaina, on Maui, where an estimated 150,000 trees burned, replanting efforts so far have focused on fruit trees that will eventually provide food and shade again, said Duane Sparkman, chair of the Maui County Arborist Committee and cofounder of Treecovery Hawaii, a nonprofit focused on replanting Lahaina.

So far, Treecovery Hawaii has raised half a million dollars to purchase trees at full price from local nurseries and give them to families who are rebuilding. The organization has established several hubs to grow more trees, and Sparkman said he’d like to buy a larger nursery space on central Maui. A detailed planting plan created by Maui County lays out what types of trees should get planted on the island, as well as the care they need.

Over 200 trees have been planted or are in pots on-site, ready to be put in the ground. That includes a mouthwatering array of fruit trees — mango, jackfruit, starfruit, avocado, citrus, and banana — fragrant plumeria and orchid trees, and native species like wiliwili, milo, koa, and lauhala trees. “Knowing that we’re going to be part of what’s eventually going to be the canopy for our grandchildren is immense for us,” Sparkman said.

Courtesy of Duane Sparkman / Treecovery Hawaii

Like in Paradise, FEMA removed contaminated topsoil from Lahaina. But other than that, Sparkman said, federal agencies provided no guidance for how communities should replant their neighborhoods. Sparkman suggests new fruit tree owners wait a few years for crops to cycle through any residual toxins that may still be in the soil.

Ulu, or breadfruit, trees were especially important to preserve post-wildfire. Breadfruit is a starchy staple food in the South Pacific and throughout Hawai‘i. “It’s been planted beside houses, and it’s been giving people food security, especially in urban areas,” said Kaitu Erasito, the breadfruit collection manager at the Kahanu Garden in Hana, Maui.

Some breadfruit trees survived the flames, growing new shoots nine months post-fire. But more will need to be replanted in the years to come. Roots from three varieties that grew in Lahaina’s burn scar were dug up for safekeeping, eventual propagation and replanting, at the National Tropical Botanical Garden on Kauai.

Lahaina’s approach to replanting neighborhood trees has been so successful that people impacted by the Dixie Fire in Northern California in 2021 reached out to Sparkman for advice and ideas. Now, there’s a Dixie Tree Canopy Restoration Project back on the mainland that plants trees for wildfire survivors for free. “Each community,” Sparkman said, “has the ability to create their own recovery.”

That recovery is already underway in Altadena. Recently, a woman whose home and community garden space burned in the fire came to Raj looking to begin again. Thanks to donations, Raj was able to provide her neighbor with all the same seeds she had lost.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline What it takes to regrow a community after wildfire on Feb 13, 2025.

As it recovers, Altadena finds inspiration in other wildfire-devastated communities that have replanted lawns, gardens, and green spaces with fire-resistant native species. Cities, Solutions, Wildfires Grist