A lot of schools talk about increasing student agency.

“Creating self-directed learners.”

“Building lifelong learners.”

“Cultivating global citizens.”

But when you walk into many of their classrooms, learning looks pretty much the same.

A teacher stands tall at the front of the classroom referencing information on a smartboard or rolling TV monitor, talking to kids seated neatly in rows. Sure, the medium for delivery might have changed; with slick, AI generated slide decks, Nearpod or Edpuzzle to help deliver more interactive lessons, and laptops in front of each learner; but the focus hasn’t.

The teacher is still the focal point, and the lesson is the same.

In my work with aspiring agentic schools around the world, and thought leaders in the field (including High Tech High), I have identified and curated a list of 12 shifts toward designing a student-centered and agentic classroom and compiled them in a forthcoming book, Where is The Teacher: The 12 Shifts for Student-Centered Environments. My hope is that by sharing how agentic schools are applying these 12 shifts within their context, it provides you with the confidence to make your classroom more student-centered as well.

Shift #1: From Teacher-Designed to Co-Designed

Ancient Civilizations were former upper elementary teacher and instructional coach Linda Amici’s of Westerville Ohio City Schools most dreaded set of standards. As she states, “They didn’t excite learners. They saw no relevance to their lives.” Through a simple reframing of how she designed the unit, suddenly, they did. Through a Google form, she asked students what civilization they wanted to learn about. Which questions and topics excited them? She co-crafted a more relevant question (What impact do contributions from the past have on our lives today?), and criteria for how students would be evaluated- which included rigorous curriculum standards. After six weeks of student-centered learning, her students transformed her classroom into a museum to showcase their creations. Some shared fashion tips and re-created clothing items from the Ancient Greeks, while others re-enacted battle sequences from the Persian Wars. Students were suddenly empowered and agentic, and as Linda put it, “even the 6 foot 10 superintendent” was impressed.

Questions for Reflection:

Before introducing a new topic, how might you discover what your students are interested in learning about?

How might you offer more choices or a menu of options around what students create to demonstrate their learning?

How might you work together to unpack curricular standards and weave them into your student’s individual projects?

Shift #2: From Led by Content to Led by Inquiry

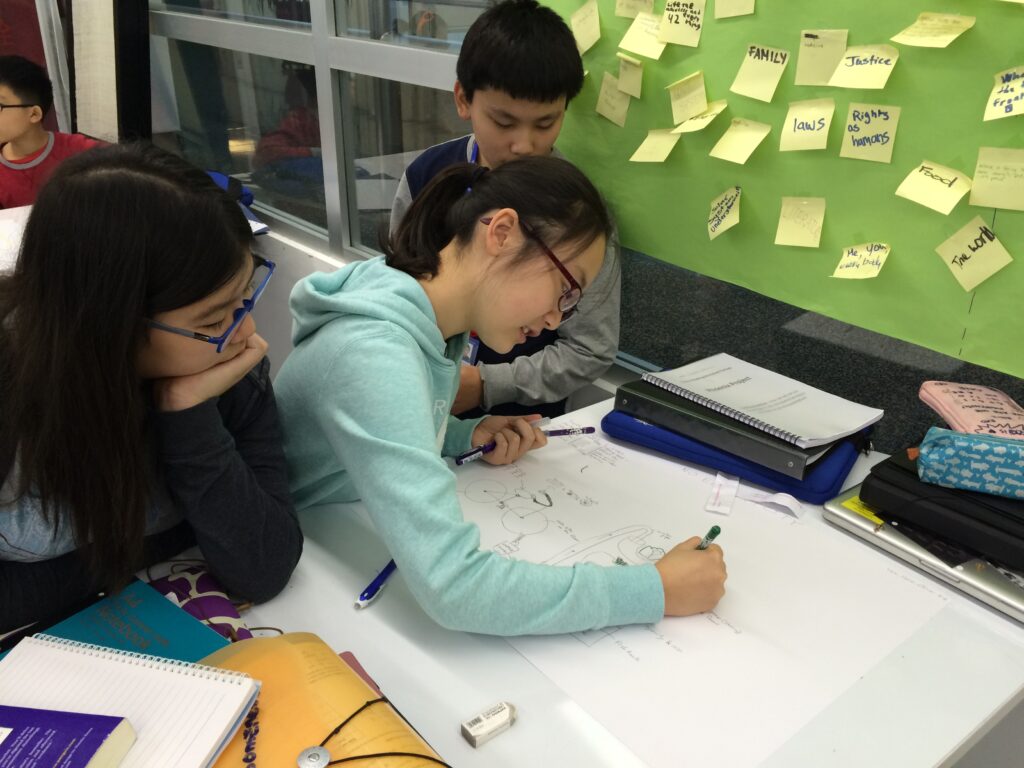

Imagine fifty students huddled together in an abandoned field outside of their school. This is how the 6 week long inquiry-based experience entitled ‘Phoenix Project: Rebuilding Society’ began at The International School of Beijing. And it wasn’t guided by a textbook. It was guided by inquiry around how these year 7 students would rebuild society after being leveled by a devastating earthquake. In small teams, they would explore possible food growing techniques, government and economic structures, and a code of ethics to present to an overseeing panel of their peers. What was the teacher’s role? To set up the milestones and guide the experience behind the scenes. Facilitators Brendan Riley, Houming Jiang, and I introduced relevant anchor texts, held small mini-lessons/workshops, and supported student teams in formulating inquiries and finding answers. As a result, students transformed from passive learners into real city planners.

Questions for Reflection:

How might you take a topic you teach and transform it into an open-ended question?

How might you organize lessons and content to support students in answering the big question? What 3-4 milestones might you set up to help guide the experience?

What inquiry/visible thinking routines might you use to make student questions visible? (Check out Havard Ground Zero’s Core Thinking Routine Toolbox)

Students inquiring around pros/cons of possible methods for food production and governance in the ‘Rise from Phoenix Inquiry Experience.’

Students inquiring around pros/cons of possible methods for food production and governance in the ‘Rise from Phoenix Inquiry Experience.’

Shift #3: From Teacher Questions to Student Questions

“To what extent has sustainability reflected on the modern Chinese fashion trend?”

“How do foreign ideas affect Chinese art through social media?”

“What are the socio-environmental impacts of rapid urbanization on vulnerable populations in China, and how can sustainable urban planning and policies mitigate these effects?”

“How would we present traditional cuisine in different regions of China, and how they have changed recently, to a High School Audience?”

These were all questions generated by students as part of a Modern China unit in Andrew Morrissey’s year 10 classroom at Beijing City International School. Students formulated questions; teamed together to explore them; and developed authentic products and presentations to address them. Some teams created video blogs, others interactive websites, some documentaries, and even more informational videos. As he put it, “[previously] they found no relevance to the unit in their lives.” To support students in exploring their own inquiries, Andrew developed an online Group Action Plan and Process Journal to document research; share evidence of newly gained skills/knowledge; and reflect on each relevant lesson. Andrew moved from the sage on stage to a gentle guide on the side. The result of making this shift to student inquiry according to Andrew? “They gained a new appreciation for their own culture, built resilience, and connected their topics to concepts in other subjects like Science and Language.

Questions for Reflection:

How might you capture student inquiries and questions for a topic you have to teach?

How might a process journal or guide help support them in addressing them?

What visible thinking routines might help students develop their questions? (Harvard Project Zero Thinking Routines)

Student generated inquiry questions from BCIS around ‘Modern China’ Unit

Shift #4: From Isolated, Siloed Content to Interdisciplinary Content and Skills

A sharply dressed 12-year-old with thick-rimmed glasses and a wide smile guides a team of international educators from table to table in her flexible classroom; showcasing architectural models, blueprints and polished presentations from her class of citizen scientists. This is not an unusual Friday afternoon at Verso International School. They receive regular visits from educators around Asia eager to learn more about how they integrate learning across multiple subjects. And their students are the ones doing most of the talking. In this particular example, a student ambassador shares the interdisciplinary work they are completing around designing their future boarding school. She articulates the different systems teams of peers are in charge of developing, from a waste management plan to energy consumption. Their challenge is to develop a viable, closed loop system to present to the team of architects tasked to build it. The experience integrates Math, Science, Language and even Art.

What are her teacher’s roles? To facilitate mini-lessons, workshops and activities to help students understand how to infuse the subject-specific content into their authentic proposals and projects. Educators at Verso have given up their ‘teacher’ title in exchange for a more student-centered one: ‘Learning Designers.’

Questions for Reflection:

What connections are possible between your content and another subject/discipline?

What big topics might you collaborate around with a teacher outside of your subject area? Consider topics like sustainability, identity, community, globalization, etc.

How do experts in the real world use your subject? How might you engage students in similar work?

Students presenting future boarding school concept and interdisciplinary systems involved at Verso

Shift #5: From Working for a Grade to Pursuit of Interests and Real-World Problem

Two very real problems faced Budapest, Hungary back in 2022. How do we provide relief for Ukrainian Refugees? And, amidst rapid urbanization, how do we live more sustainability?

And rather than approach the typical year 5 curriculum from an educational lens, Real School Budapest decided to approach it from the lens of these real world problems. Dave Strudwick, former learning leader and head of school took his informative writing standards, parts of his science curriculum, and even visual arts and dance standards and merged them together in a five-week expedition around sustainable fashion. Students developed an online digital magazine exploring the ‘hidden costs’ of fast fashion, from its pollution of oceans and filling of landfills, to cost of human labor and exceeding energy use. Students also put together a fashion show to model upcycled outfits and exhibit their work, collaborating with real fashion designers and journalists along the way. All proceeds from the big show went to fund Saturday School English classes and other workshops for Ukrainian refugees who arrived in Budapest just four days after the invasion.

Dave says when students are working to solve a real problem, “the classroom literally disappears because students are so absorbed in what they are doing.” His role? The same as it would be if he were guiding work outside of the classroom: “Take students through a proper design process, where they are constantly iterating, and getting feedback from a real client.”

Questions for Reflection:

What real world problems are relevant to your curriculum?

How might you use the context of real issues in your community to inform learning in your classroom?

How might a design process help guide student-centered work?

Student-produced sustainable fashion magazine cover for Real School

Shift #6: From Worksheets and Tests to Real Product/Service

Two 9-year-old students from KPIS International School lean in across the table to listen to a same-aged peer talk about his favorite hobbies. The conversation is in Thai and has a clear purpose. In addition to helping forge new relationships and connections, these international school students are hoping to design English learning games, resources, and activities around their peers’ greatest areas of interest. It’s part of a deep dive to make language learning more purposeful, organized by their classroom teacher Tony Pasaud. Students will still learn grammar rules, vocabulary, sentence structure, dialogue rules and other mandated English curriculum, but learn through developing a real product for real people. In true, student-centered form, Tony will hand over his ‘teacher hat’ to his learners. His new job will be to facilitate the process; organize student teams; deliver mini-lessons around the English content students will transform; provide feedback on their work; and share criteria and rubrics to ensure it is high quality.

But it’s not just Tony’s class that’s shifting from worksheets to real products/services. Students in the classroom next door are developing stop-motion films to better understand wellness. Across the hall, students are building small businesses to learn math. And downstairs, students are constructing gardens to learn environmental science. They are doing real-world work, and they are only 5-12 years old.

Questions for Reflection:

How might you offer more choice in the work students create in your classroom?

Who is the beneficiary for student work? How might you connect to a beneficiary outside of the classroom?

Who are some real world experts that use your discipline/subject? How might you connect them to your classroom? With students?

Shift #7: From End of Learning Reflection to Ongoing Reflection on Process and Product

Student-Centered Facilitator Alfie Chung of the Social Innovation Wing of Polytechnic University addresses his year 12 students: Who are you designing for? Are you designing for yourself or Fitness Trail Users? What kind of problems are you noticing? What did you learn from interviews and observations? What have we accomplished so far, and what’s left to do?

In student-centered environments, reflection is not an end of learning exercise, but an ongoing process, and the role of the facilitator is to ask the right questions. In the example above, Alfie asks reflective questions around what students are learning from their investigation of user behaviors at the park across the street. This is stage one of a five-stage design process. Students will undergo four more reflective cycles before sharing their final designs for the new play area to the department tasked to build it. Through a reflective journal, students capture their thinking, drafts/iterations, peer and user feedback, and research. Beyond journals, Alfie uses portable whiteboards to track progress: “I never erase the whiteboards. These whiteboards become like artifacts to keep track of our journey. Every week before we start lessons, we look at them to reflect on what we have already done.”

Questions for Reflection:

How often do you reflect with learners? How might you make reflection more of an ongoing process?

How might you increase ownership over student reflection?

What mediums do you provide for reflection? How might you increase ways in which students reflect?

Visible student brainstorming and ongoing reflection for the the Park Redesign at Social Innovation Wing PolyU

Shift #8: From Independent Work to Collaborative Tasks

“We were reading a book about a bunch of rich, white people in the 1920s and we work in Southeast San Diego with mostly students of color, lower income.”

Above is an honest reflection from two Year 10 Literature Teachers at Gompers Preparatory Academy, a student-centered charter school in one of the most impoverished regions in San Diego. The Great Gatsby was part of the curriculum but had no relevance to student’s lives. So Dave and Michelle decided to give it a student-centered twist. Students would still read the novel, but instead of writing independent book reports, they would decide collectively how they would apply lessons to their lives. After learning that one bubbly girl already had her own successful podcast and YouTube channel, the class decided on a class podcast. Each episode would share how the “American Dream” had changed from the 1920s, using stories from their own community to illuminate the theme and compare it to the one found in the novel. Students worked in small teams to produce each episode; dividing roles, tasks, and written and audio content. Dave and Michelle’s role? Support all teams with a project timeline, group folder to track progress, a school website where they could publish their work, and checklists and graphic organizers to organize their thoughts.

Tables were rearranged into small groups, and recording and production equipment lined the exterior. The space transformed from a classroom to a production studio. The Great Gatsby finally had meaning. From Michelle: “It’s the most meaningful thing I have done as a teacher.”

Questions for Reflection:

How might teaming students increase motivation and engagement in your classroom?

What assignments might you turn into group tasks? How can you provide choice in team roles?

Shift #9: From Teacher-Led Discussion to Student-Led Discussion

How can the most innovative square mile on the planet be plagued by racial injustice only 2 blocks away?

This is the big question guiding work by young ‘Innovators For Purpose” (IFP) across schools in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Students are building installations, publishing books, creating augmented reality simulations, and developing educational games. And they are using a simple, but profound student-led discussion tool to guide them. Developed and facilitated by pioneering educator Ela Bur, the ‘innovator’s compass’ uses five questions to guide young people in getting to the heart of issues:

Middle Quadrant: Who’s involved?

Observation Quadrant: What’s happening/why?

Principles Quadrant: What matters most?

Ideas Quadrant: What ways are there?

Experiment Quadrant: What’s a step to try?

A student facilitator guides the discussion while a student notetaker captures ideas on post-its and places them in each quadrant. Ela’s job? Model the process, clarify student roles, and ask probing questions. By using a repeatable framework and protocol for discussion, Ela is transforming once passive learners into active citizens.

Other discussion protocols include socratic seminars, fishbowls, jigsaws, and democratic circles.

Questions for Reflection:

What discussion protocols might help you amplify student voices?

How might you provide more leadership opportunities for students in class discussions?

Shift #10: From Progress Assessed by Teacher to Self, Peer,

Expert Feedback and Critique

Student-Centered Practitioner Gary Heidt, English Teacher and founder of Nova Lab, was tired of students “checking achievement boxes, climbing each ladder to get to the next.” As he states, “it was not about learning.” He did something radical in response. He eliminated grades entirely; replacing tick boxes with a system of ongoing feedback, narrative comments, and peer review. Students would only receive a pass/fail mark. The result? Learners articulated their learning and took greater ownership of the process. As Gary retells, during ‘learning pitches’ around writing and publishing stories, learners detailed their process of advancing from initial storyboard to developing plot and characters; referencing how feedback and revision guided each successive draft; in small business proposals, how they established their business idea and how expert mentor feedback informed their work to bring it to market.

Gary’s role? Build in time and structures for high-quality feedback and critique. He modeled protocols like T.A.G.; demonstrated how to elicit feedback through Google Forms; and held 1:1 conferences with students to establish personalized goals, and action steps to reach them.

Student presenting Learning to Panel of Peers and Experts at Nova Lab

Questions for Reflection:

How can you make learning less ‘tick boxy’ and more narrative in your classroom?

What time might you carve into class for peer feedback and presentations of learning? What effect might it have on student ownership and empowerment?

Shift #11: From Teacher Audience to Authentic, Public Audience

What happens to student engagement and empowerment when they are given an authentic audience to present their work?

This was the big question behind the founding of VIS Better Lab School in Taipei. Students are sharing plans to make bus stops more inclusive with the transportation department. Proposals to improve water quality at the nearby river with the local water authority. But perhaps the most agentic of all these extended learning experiences is the 100% student-run VIS radio station. On a regular basis, students film, edit, and publish episodes to their Youtube Channel, and each student plays a role. Some are in charge of the camera work; others, lighting; some, the interviewing of guests; others, post-production work; and even more, branding the episodes and increasing subscribers. They have explored topics ranging from the history of R&B to the progressive schooling movement. At public exhibitions in a highly visible public space in Taipei, students share their learning within each of these ongoing projects, and what the local community can do to get involved.

So where’s the teacher? What’s their role? Their learning ‘facilitators’ as VIS calls them can be found supporting teams; helping mitigate conflicts; holding whole class reflections; building task boards; and delivering mini-lessons on interview techniques, lighting, camerawork and audio. Byron Clarke, one of the lead facilitators shares, “When students are working on something they care about, I don’t have to do as much.”

The impact? Student empowerment skyrocketed. From a student: “I love doing projects. I love being involved. I love being more active and proactive in my learning.” – Flora Lin, VIS Learner

Questions for Reflection:

What authentic audiences for student work exist outside of your classroom? Who in the school might students present to?

How might students expand the audience for their work and learning? Digitally and in-person?

Students exhibiting project work at VIS Better Lab School Taipei

Students exhibiting stories from youtube channel and VIS radio station

Shift #12: From Classroom Based to Community-Centered Impact

Imagine if for two lessons a week, students left the silos of their subject-based classrooms, and instead worked on applying cross-disciplinary knowledge and skills to address Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). That’s exactly what will happen in the 2024-2025 school year for all Year 7 students at Bangkok Patana School. Two subject teachers will combine around each goal to design experiences that provide students agency in investigating and devising solutions relevant to their community. Some students will investigate minority groups and showcase the unique customs, traditions and culture of marginalized groups in Bangkok to address SDG #10: Reduced Inequalities; while others investigate the local ecosystem and estuaries and build wire sculptures of animals to make life below water more visible on the surface (SDG #14). The hope is that by providing these experiences, students will become more active citizens within their community, and see that they can make a difference.

Their teacher’s role? Each subject teacher will strategically scaffold the experience through mini-lessons, activities, articles, and field trips to better understand the issue from their subject’s lens, while also supporting students with their authentic solutions.

Questions for Reflection:

What connections might you build for a current unit of study to larger Sustainable Development Goals?

How can you allow for more field trips, and hands-on experiences in the community within current units, topics, or lessons?

Call To Action

Let’s return to that teacher-led classroom we illustrated at the beginning. Except now, let’s imagine it is filled with agentic learners who take charge of their learning. In the corner, a peer shares his scientific drawing on a rolling tv screen while his peers provide specific feedback. At the counter in the back, two students in lab coats examine slides of local water samples under a microscope. In another corner, six students huddle in a circle to discuss an article they annotated the night before. At standing desks in the middle, three students add slides to their team’s pitch deck. Their teacher crouches next to them, probing into how they might make the message more clear.

This is not a hypothetical scenario. It’s a real depiction of what is happening in agentic classrooms around the world. And it’s not too far out of reach. In the age of AI, data, and information at our student’s fingertips, our role in the classroom must shift to allow for it. Which of the 12 shifts will you make to get started?

The post 12 Shifts to Move from Teacher-Led to Student-Centered Environments appeared first on Getting Smart.

Kyle Wagner observes 12 fundamental shifts that can take a classroom from being a teacher-led experience to an engaging student-led one.

The post 12 Shifts to Move from Teacher-Led to Student-Centered Environments appeared first on Getting Smart. Equity & Access, Learner-Centered, design thinking, guidance and support Getting Smart