This story about talking to kids was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education, with support from the Spencer Fellowship at Columbia Journalism School. Sign up for the Early Childhood newsletter.

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. — When Rickeyda Carter started teaching young children, she led story time the way she remembers being taught as a child. That meant children were expected to sit, listen — and remain silent. “When the teacher is reading, you don’t talk,” Carter recalled.

Carter didn’t think anything of this approach for nearly a decade, until the program where she was employed, New Rising Star Early Childhood Development Center, opted to participate in an initiative aimed at improving the interactions between teachers and children in their care. For 10 weeks, the 3- and 4-year-olds in Carter’s classroom donned miniature vests with “talk pedometers” nestled inside, meant to track how often children and their teachers converse. Carter received weekly coaching and data on how much, when and with whom she was talking in her classroom. As she learned about the science behind why those conversations are so important, Carter realized she wanted to change things.

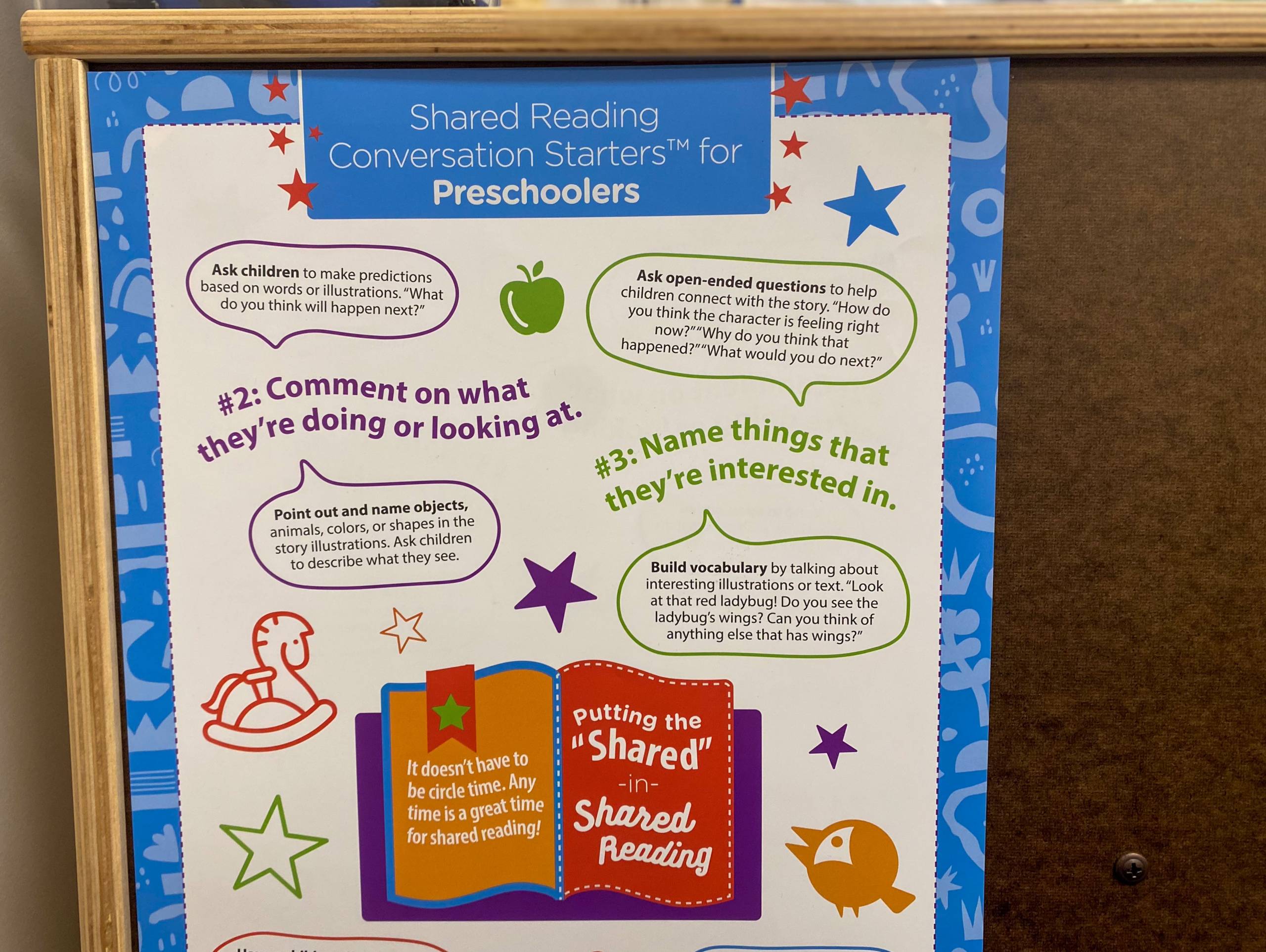

Carter started talking more with the children, especially during meal times and after they woke up from naps, times when the pedometers showed she wasn’t interacting with them as much. She prioritized connecting more with children getting the least attention. She revamped story time to make it more interactive.

“I’m learning that it’s OK for them to interrupt in the middle of a story and ask questions,” she said. Those changes made a difference. Children quickly became more engaged in activities and seemed to learn more, Carter said, especially when it came to literacy and reading comprehension.

For child care programs, the strength and frequency of these myriad interactions between a caregiver and a child are central to quality. Babies need stimulation from a caregiver who talks frequently and responds to their sounds and cues. Older children, experts say, need thoughtful questioning and responses that help develop critical thinking skills and vocabulary.

A growing number of cities, states and individual programs, including Texas, Virginia, Mississippi and Washington, D.C., are pouring resources into training teachers and evaluating programs on how warm and responsive teachers are, including how tuned-in they are to the children’s needs. The trend crosses traditional political divides. Cities including Providence, Rhode Island; Virginia Beach, Virginia; and Birmingham, Alabama, have funneled money into the program used in Carter’s class, created by the nonprofit LENA, which focuses on improving early talk and responsive relationships among caregivers. Large child care chains like KinderCare have revamped their teacher training programs to add a greater emphasis on teacher-child interactions. And one state, Louisiana, has gone all in, making interactions the sole focus of how it assesses child care quality.

“Of all the things that matter in children’s experiences in a classroom, nothing is more important than the relationships and interactions that they have with the educators and other children that they spend time with,” said Bridget Hamre, a research associate professor at the University of Virginia who co-authored an early childhood classroom scoring system that rates teacher-child interactions. Other elements of quality, like teacher education and ratios, are “only important to the degree to which they change the way that teachers interact with kids,” she added.

The type and amount of talking and play between teachers and children is critical because the brains of infants, toddlers and preschoolers develop faster during the years in which they are in child care than at any other time in their lives. Those brains grow through a process scientists have coined serve and return, when a caregiver and a child engage in back-and-forth exchanges like a “lively game of tennis,” according to researchers at Harvard University. This banter is so powerful, it helps strengthen circuits of the brain and creates the building blocks for language, social skills and other cognitive abilities. High-quality child care with nurturing, responsive interactions can positively impact a child’s school readiness, working memory, behavior, academic development, and social and emotional skills.

Nationwide, research has found many caregivers struggle to provide ample, responsive interactions. National data compiled by LENA, for example, found about 1 in 4 children experience little attention from their caregivers, even in programs with high overall ratings on state quality scales. In infant and toddler classrooms, a third of children in the classrooms LENA has worked with experienced so few interactions per hour, they essentially spent the majority of their day in isolation.

In Birmingham, where Carter teaches, the city has invested more than $1 million into a nonprofit, Small Magic, which runs a program using the LENA pedometers called “Birmingham Talks.” Since 2019, the program has coached more than 400 teachers in more than 60 child care programs in the area, including center-based and home-based settings.

Educators who have participated in the program say it’s had a deep impact. Many thought they were interacting equally with all children but realized that wasn’t true upon seeing data from the LENA devices. That’s especially the case, educators say, with children who are quieter and may not get as much attention as those who naturally speak more or who present as a behavior challenge.

Many child care providers cite the relationships with children as their favorite part of the job, but the realities of working in a child care program in America often complicate teachers’ best efforts to devote time to nurturing, one-on-one relationships.

Child care teachers are often responsible for large numbers of children and paid poverty-level wages. Many are grappling with more disruptive child behavior than prior to the pandemic. “The reality of being an early childhood teacher right now is so incredibly stressful,” said Hamre. “It makes it hard to prioritize those kinds of interactions when … you are supporting children who are coming in with so many challenges of their own,” she added. “Stress really reduces everybody’s capacity to invest in the kinds of relationships that matter most.”

In many communities, the situation is getting worse, not better. As pandemic relief aid has run out, many states have turned to deregulation efforts to solve child care shortages, bringing in less-experienced workers, cutting training requirements and increasing the number of children staff can watch on their own. And while deregulation efforts are typically championed by Republicans at the state level, they’ve gotten some conservative pushback. “There are important dimensions of early-childhood education and childcare that just can’t be deregulated away. Young children need close adult supervision,” wrote Frederick M. Hess and Michael Q. McShane of the conservative American Enterprise Institute in a 2024 early childhood policy report. “Removing regulations can certainly help on the margins, but that requirement won’t fundamentally change unless we want AI reading stories and robots monitoring playtime.”

In Mississippi, which has one of the highest staff-to-child toddler ratios in the country, Jackson-area child care director Lesia Daniel said relationships become more challenging as the number of children increases. “Can you imagine being in a room with 12 2-year-olds who are not potty trained by yourself every day?” Daniel said. “I mean, literally all you’re doing is changing diapers and trying to keep them alive.”

Daniel has provided training to her staff to help them learn the nuances of how to interact most meaningfully with young children. Instead of asking a question like, “What color is your car?” Daniel said questions should nurture vocabulary development and critical thinking skills. A teacher could ask: “Who’s riding in your car? Tell me about those people.”

At Hand in Hand Early Learning Program in southwest Birmingham, an inclusive early learning center where children with and without disabilities and developmental delays learn and play together, conversations between teachers and children are detailed and deliberate.

On a fall morning, as teacher Kayla McCombs helped her pre-K students get settled in various activities around the room, one of the children summoned her to the small play kitchen in the corner of the classroom. It was an opportunity to converse one-on-one, introduce the child to vocabulary and help immerse him in deeper imaginative play than he would achieve by himself.

“What are we doing?” McCombs asked as she slid into a tiny gray chair. “Are you going to cook some food?”

“Yes,” he replied.

“Oh, I’m so hungry,” she said.

“Me, too,” he replied.

“Oh, you’re going to microwave?” McCombs asked as the child carefully placed a plastic cup inside the pretend microwave.

“Yeah,” he replied.

“Is it hot?”

“Yeah.”

“Be careful! Don’t burn your hands,” she replied.

McCombs and her colleagues benefit from a smaller staff to child ratio — 1-to-6 at this age, far less than the 1-to-18 set by the state. On this morning, there were two teachers in the class, as well as an assistant teacher and an occupational therapist, all working with 16 students. That meant McCombs could focus on these interactions.

McCombs’ co-teacher, Skylar Yeager, said the data they got from wearing LENA devices revealed how some children got far less conversational time with teachers than others. Now, staff are more purposeful about prioritizing one-on-one interactions with every child.

Across the country, states including Georgia, Arkansas, Texas and Vermont are trying a wide range of ways to teach early educators about interactions and adding or expanding a teacher-child interaction component on state child care quality rating systems. All Our Kin, a nonprofit focused on family child care homes, sends coaches into programs in Connecticut and New York to support those providers in relationships and interactions with children.

Virginia has taken it even further. In 2020, state officials enacted a law requiring any early learning program that receives public funding to participate in the state’s child care improvement system, which includes a teacher-child interaction scale. Teachers in all types of programs are now observed twice a year to see how meaningfully they talk to and play with children. The data has given program officials the ability to zero in on classrooms where children aren’t having good experiences and offer intensive counseling to those teachers, said Jenna Conway, Virginia’s deputy superintendent of early childhood care and education.

There have been challenges with the sweeping initiative. It involves what Conway called a mindset shift for teachers, particularly those working with infants. Some teachers fear that if they encourage more conversation, they’ll have more classroom management challenges, said Jill Gilkerson, chief research and evaluation officer at LENA. “A lot of the time, child care can be focused on behavior, and trying to make sure that there’s not a lot of rambunctiousness, keeping the level of sound down,” she said. “I think a lot of teachers will associate less talk with a more controlled environment.”

Many programs also struggle with high rates of teacher turnover, which disrupts relationships with children. New staff then need training in how to engage most effectively.

Research out of Louisiana, the state that has done the most to prioritize interactions, provides hope that despite the challenges, that mindset shift on the part of child care teachers can improve quality. Ten years ago, under Conway’s direction, Louisiana ditched its complex quality rating system in favor of a rating scale that looked solely at interactions between children and teachers. The state also increased the amount of money providers get when they serve children from lower-income families who pay with state subsidies and funded new educator certificate and preparation programs. In the four years following these changes, researchers found a substantial improvement across child care programs in the state when it comes to such measures as the warmth and sensitivity of teachers and the language development support they provide to children.

This focus on what may seem like small, insignificant interactions has continued to positively influence other aspects of child care, Conway said. “Directors and others became smarter and more strategic about who they’re hiring,” she added. That includes recruiting educators who have the right temperament for the classroom and educating new hires on what matters under the new quality scale. For infant teachers, for example, that means, “You’re gonna talk to the baby. You’re gonna talk while you’re feeding them. You’re gonna talk while you’re diapering them,” Conway said.

“It’s those little things that I think make the difference.”

Contact staff writer Jackie Mader at (212) 678-3562 or mader@hechingerreport.org.

This story about talking to kids was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education, with support from the Spencer Fellowship at Columbia Journalism School. Sign up for the Early Childhood newsletter.

A growing number of cities, states and individual child care programs are pouring resources into training teachers on the importance of talking to kids as much as possible. MindShift