Listen to the interview with Matthew Johnson:

One afternoon in the spring of my fourth year of teaching, I sat at my kitchen table, head in hands, having a breakdown. Its genesis was that I became a teacher to help students discover their voices as writers. In that pursuit, I’d sunk endless hours over the last four years into seeking out just the right examples and mentor texts, crafting clever lessons about commas and clauses, creating funny songs about parts of speech and predicates, and assigning a lot of papers — papers that, as I have already discussed on this site, drove me to the edge of burnout.

I came into teaching with visions of Dead Poets Society or The Great Debaters, and yet, nearly four years in, I felt trapped in the opening sequence of a cliched teacher movie where students stare blankly as the teacher drones on, boredom painted on their faces.

At this point, I strongly questioned whether I was cut out to be a teacher. In a last-ditch effort to stay in the classroom, I decided to embark on a writing instruction boot camp of sorts during the summer. By day, I compared notes with other writing teachers through the National Writing Project, and by night, I read a large list of books on writing pedagogy. Over the next few months, I began to understand that my frustrations about writing instruction weren’t what separated me from other teachers; they were what connected us across location and time.

I also learned that within writing instruction, grammar is a particular problem. There is a very long and very clear history of scholarship that shows that many common approaches have minimal or no effect on student writing growth, and it is so widely disliked by students and ignored by many teachers that Brock Haussamen (2003) famously called it “the skunk at the garden party of the language arts” (p. x) in his book Grammar Alive!.

These realizations were on the one hand comforting. It was nice to know my struggles weren’t a private indictment of me as a teacher. But on the other hand, they were also deeply troubling. How could I help students to harness and express their voices if so many of the tools out there were tried but not particularly true? And why is it that grammar, one of the oldest and most practical subjects (we use it nearly every waking second to turn our thoughts into words, after all), is so ineffective and reviled?

Over the years, these questions became obsessions of mine, and nearly a decade ago I started a writing instruction-focused blog to seek out answers. Jump to today, and I now have more answers — answers I share in a new book called Good Grammar: Joyful and Affirming Language Lessons That Work for More Students.

The book looks at why grammar and language lessons are so often viewed as skunks and what we can do to make them more effective and a more joyful force for good in the lives of more students. In particular, I found three common issues that contribute not only to grammar’s skunky status but the skunky statuses of other subjects. If we can thoughtfully address these issues head on, we can get many more students to meaningfully engage with them. These changes can make the study of grammar and language effective and joyful — so much so that on year-end surveys for the last five years, students have named it as their favorite part of my class.

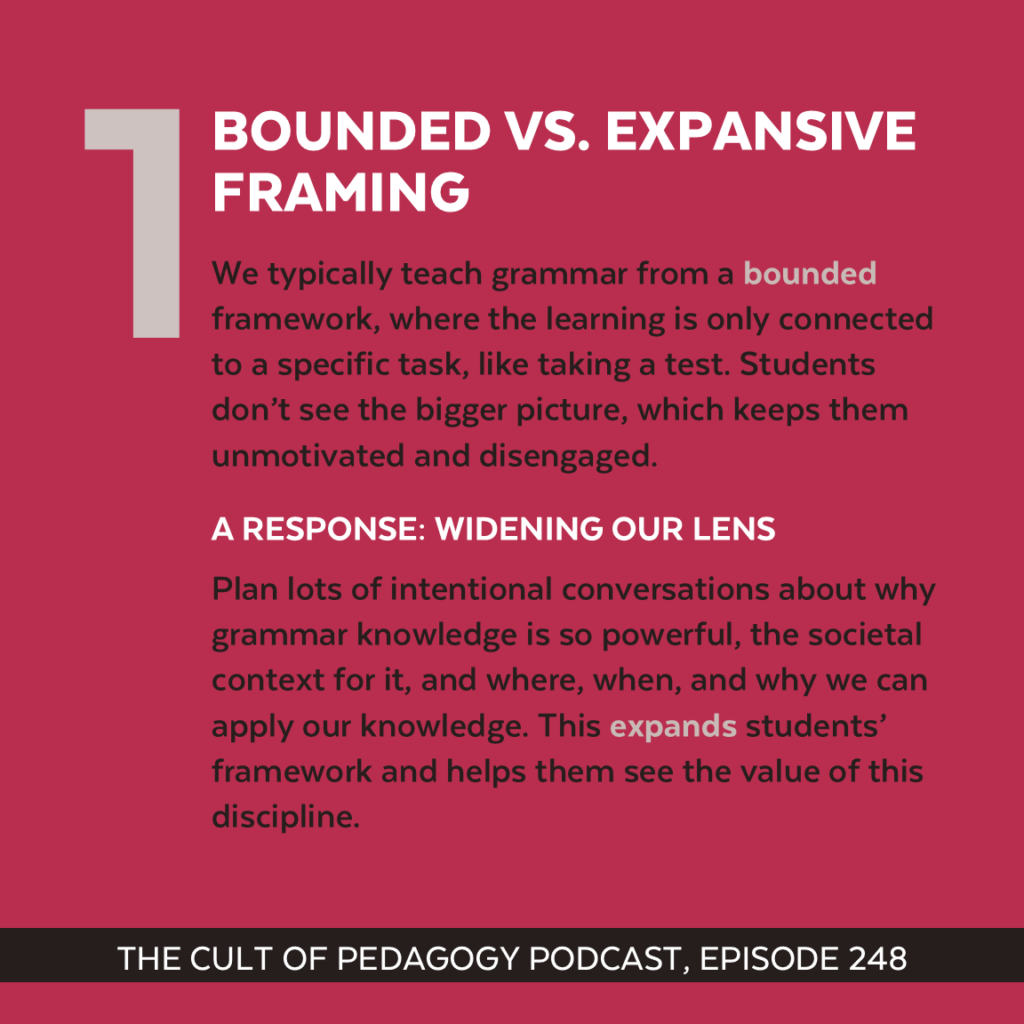

Skunky Issue #1: Bounded Versus Expansive Framing

What Are Expansive and Bounded Framing?

Even if you haven’t heard of expansive framing, you have undoubtedly engaged in it many, many times. Expansive framing is where you introduce students to the wider story and discussion of a subject: its backstory, why it matters, the debates around it, and its other applications beyond a given test or project, etc. In research circles, it is often contrasted with bounded framing, or learning that is only connected to a specific task (Engle et al, p. 215). Skunky subjects in most disciplines tend to be the most bounded. We tell students we are learning about noun appositives or trigonometry because they will need it for a test or project and leave it at that, with its wider context and uses left to the students to determine.

The Problems With Bounded Framing

Teachers often use bounded framing with skunky topics because they can be the trickiest to expansively explain. Take grammar: Many students come into my classroom unable to tell me what a predicate or preposition is, and yet they are able to intuitively use both in the production of wonderful stories and essays. This calls forth an uncomfortable question for those that love grammar instruction: If many students can already intuitively compose strong, interesting, and grammatical sentences, is grammar instruction even necessary, especially given that AI-powered grammar checkers have made it highly unlikely that a comma splice or misplaced apostrophe will slip through?

This question is not easy to answer (though I provide one later), and that is exactly why it is so important to expansively explore. If students don’t see the bigger picture, it adds huge obstacles to their learning. First, without a broader picture, it can be hard for students to use background knowledge in the development of strong schemas, which can slow understanding and retention. Further, given that perceived value is an essential prerequisite for motivation, not understanding the value of something will likely limit both student motivation and its close confidant, engagement.

A Response: Widening Our Lens

This importance of expansive framing means that before I ever mention clauses or commas, we take a wide-angle look at grammar and language. This starts with me giving my students a series of notecards with the word “the,” a random noun (maybe “cats”), and a handful of adjectives (like “large,” “three,” and “blue”) and asking them to put the words in order. For my multilingual students, I often ask them to do it with whatever language is most comfortable.

Students generally do it in a moment and almost always put them in the exact same order: The three large blue cats. Once they are done, I ask them to identify all the parts of speech in the phrase — a task that leads to no shortage of blank looks and head scratching. I then ask them a key question: Why was it so hard for many to identify the parts of speech when you were able to automatically use them at such a high level that you knew that when dealing with adjectives, a determiner (the) comes first before quantity (three), which tends to come before size (large), which in turn usually comes before color (blue)?

This begins a conversation we have all year about the purpose of grammar and language instruction when we already bring so much intuitive knowledge to the table. In this conversation we talk about everything from how they acquired their knowledge to why it is still important to learn some grammar terminology. We also engage in discussions about dialects and idiolects, code-switching and code-meshing, and many other topics often reserved for college linguistics classes that my students can manage remarkably well. All of these conversations throughout the year help to paint an expansive picture for them of what grammar and language instruction is about and to make clear its value and applications.

Maybe my favorite of these discussions from this year happened when we looked at Apple’s Apple Intelligence, Grammarly’s Words that Work, and Google’s Infamous Dear Sydney commercials and discussed the messages these tech companies give us concerning our writing and how students felt about those messages. In the end, all five sections of my classes quickly recognized that while the ads disparage our voices as being lesser to AI-airbrushed voices, the reality is that those who can use grammar and language knowledge to fully express their unique voices will stand out versus the host of similar AI Stepford voices out there — a realization that has proven to be a huge motivating influence for my students all year long as we do the hard work of making our way through everything from appositives and apostrophes.

Skunky Issue #2: Siloed Instruction

What Is Siloed Instruction?

In the 1990s, writing teacher Constance Weaver recognized something important. She found that while her students were able to do grammar worksheets just fine, they struggled to apply the understanding from those sheets in their own writing. This observation led her to stop teaching about grammar and language in isolated worksheets and to move the lessons into the writing students were already doing for class. This move towards teaching grammar “in-context” might seem somewhat minor, but what Weaver understood in that moment is that siloed information — which is to say unconnected information — can be a serious detriment to student understanding and ability to use it. In the words of Blake Harvard, our brains are “spiderwebs of knowledge”; we understand everything through connections, and so when information is presented as a standalone silo, it can be hard to understand, remember, and use.

The Further Problems With Siloed Instruction

If we look at instruction, information in our classes can be siloed in several different ways. One is that different topics within our classes can be presented separately, like they are from completely different species instead of branches of the same tree. In the book Learning That Transfers, Stern et al. (2021) explain that we often do this because we are experts who see how everything in our class connects. We can see the whole tree so clearly that we forget to make its connections clear to our students, who, being novices, might not see the connections at all. Here is how the authors put it:

“[Experts] gaze into the night sky and immediately see constellations that give shape and meaning to each star — they see Ursa Major and Orion’s belt — whereas their students gaze upon the same stars as random points of light” (pp. 8–9).

Along with not making connections clear, content can also be siloed in time. It is incredibly common for teachers to discuss a grammar/language concept once in a mini-lesson, and then move on, never speaking of it again.

Siloing across content and time have a similar problem: We as humans are designed to forget more than we are designed to remember. Memory and attention are precious resources, and if something doesn’t connect to our background knowledge and only pops up once for a brief moment, it is unlikely the brain will commit the necessary resources to learning it well, learning it long-term, or learning it at all.

A Response: Careful Organization

The organization of many grammar curriculums in English can be traced back to what is commonly recognized as the first modern English grammar book, Robert Lowth’s A short introduction to English grammar with critical notes from 1762. Lowth broke his book into an organizational structure that is likely familiar to many: parts of speech followed by sentence structure followed by punctuation. This organization is fine for teaching students to recite what a conjunction or colon is, but, like Constance Weaver recognized, it does little to help students use that information to improve their own writing or reading.

In her wonderful book Writing Rhetorically, Jennifer Fletcher argues that “the application of prior knowledge and skills to new tasks and contexts [is] the holy grail we seek as educators” (p. 20), or in other words, the ultimate goal of education isn’t just learning something; it is learning how to apply that something to tasks students face in the future. And a key to this is how we organize our curriculum. If we can make the connections in our curriculum clear — while also revisiting key topics in multiple thoughtful ways — it can help students to better retain that information and understand how to transfer it to new tasks.

Part of this is eliminating unnecessary divides — for example, the way Weaver eliminated the gap between worksheets and student writing. Another key is thinking deeply about our overall organization. I now organize my grammar units based on usage, not classification. This means instead of having units on parts of speech and punctuation, I now have units on the tools we have for adding emphasis or expressing one’s voice. This can make for some strange bedfellows (for example, colons are presented with purposeful sentence fragments as tools for emphasis, while their keyboard cousin the semicolon comes later when we talk about sentence structure and voice), but it makes a huge difference in helping students to connect and apply the information. I also make sure that once a concept is introduced we revisit it at least five times at a minimum.

To see this in action, let’s take the colon. I’ve found students can fairly easily learn enough colon basics to do well on a worksheet, and yet if we stop there, most students never use colons in their own writing or really understand why authors use them at all.

That is why I now place colons in my unit on emphasis, as it is indeed an emphatic tool. And before we even get to colons, we talk about why emphasis is important. I do this by having them get their phones and look for how they add emphasis while communicating through texts or social media. We then make a big list of what they do and talk about how humans are expressive, emphatic creatures who find ways to add extra energy to all forms of communication.

When we finally shift to discussion of colons, students already understand that it is one tool in the wider category of emphasis tools and why these tools are important. Then we discuss the purpose of colons — how they mimic the long pause we take before verbally saying something important to draw attention, how they impress readers, and how they can help our writing to stand out from AI writing, which struggles to use emphasis tools well. Students then explore their favorite authors and websites for colons and we use what they find to discuss the nature of the colon. Lastly, students go and put them in their writing, and by this point many get so enamored with the colon and use it so much that I sometimes even warn them to use it slightly more judiciously.

Skunky Issue #3: Feeling Incompetent

The Problem with Feeling Incompetent

In his book Embarrassment, Tom Newkirk gives a theory for why writing is so hard to teach and to do. He states that writing is difficult for us and on us because “as social beings we feel an obligation to act in a competent way.” Anyone who has written for any length of time likely knows that writing is largely an exercise in feeling incompetent.

Skunks in other subjects often evoke heightened feelings of incompetence too. I can recall hating trigonometry in high school because I was bad at it and math largely made sense up to that point. The truth is, the skunks in our schools are often hard and require one to go through a gauntlet of incompetence and errors before emerging as competent. While we may talk a lot these days about the importance of struggle and being ok with mistakes (both good things to discuss), it doesn’t mean struggle and mistakes aren’t still uncomfortable and embarrassing at times. And if we aren’t careful, those feelings slow or shut down the higher-order skills needed to make it through those difficult topics.

A Response: Curiosity and Joy

In early 2020, I attended a workshop called “Teaching for Joy” where storyteller and professor Kevin Cordi pointed out that we often think of joy in the classroom as an either/or. We can do something meaningful OR fun. We can do the work OR seek joy. Cordi spent his session disproving what he called a ”false dichotomy,” pointing out that joy and its cousin curiosity can do the following, if well used:

- improve student work and understanding

- increase student motivation

- decrease the stress levels of both students and teachers

Joy and curiosity can also be particularly powerful antidotes to the shame that can come with feeling incompetent at something. And with all of its Latin terminology and endless layers of exceptions and footnotes, it is very easy to feel incompetent concerning grammar.

But how to make grammar and language instruction joyful and curious? One key is to regularly remind students how much they already know. We can also remind them that the purpose of learning grammar is not just about fixing errors — it is to learn how to express ourselves more fully and clearly.

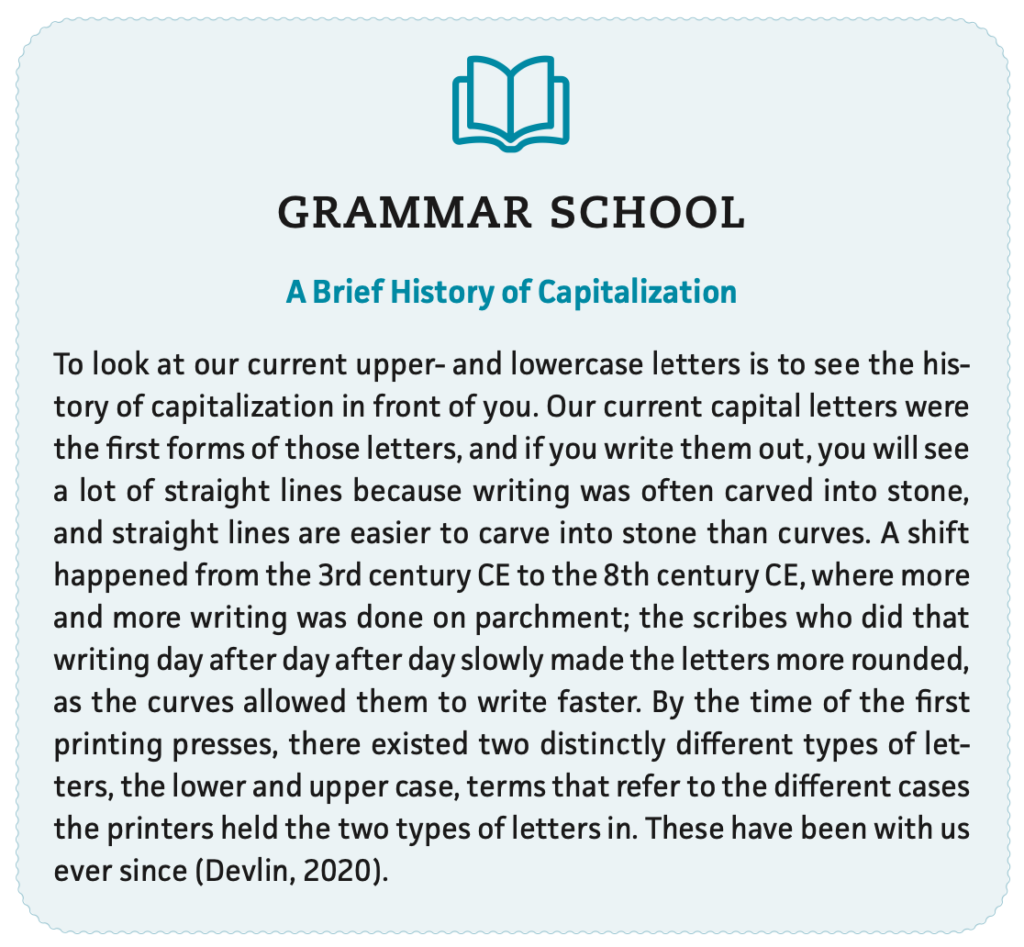

To see this in action, let’s look at capital letters. Capitalization is often taught as a series of rules students are supposed to follow, but it is so much more. It is worth noting that many languages, including Arabic, Japanese, and Hebrew, don’t have capital letters. Capitals are a historical oddity (see box), but they now come with certain common conventions.

With this in mind, I start my capitalization instruction by telling students that many languages don’t have capital letters, but since English has capitals now, speakers of English have developed certain uses for them. We talk briefly about the common conventions taught in school (capitalizing “I,” the start of sentences, and proper nouns).

I then tell students that beyond those conventions capitals live very interesting lives in the wider world. There are those (both today and in the past) who use no or almost no capitals, others follow the rules taught in schools all/some of the time, and still others use tons of capitals or even ALL CAPS at times. And it isn’t always who you’d expect: McDonald’s switched from regularly using all caps for their outdoor signs to the “i’m lovin’ it” slogan that has gone on for 22 years strong without a single capital.

Students then explore capitalization usage online and bring back screenshot artifacts that point out how people in the wider world use capitals in surprising ways. From these I’ve learned everything from the fact that musicians tend to announce hot new album drops with all caps to the fact that the Washington Capitals hockey jerseys are ironically written in all lower case. This discussion of capital usage ends with each student writing a short piece about how they see themselves using capitals in and out of school.

In the end, this curiosity-driven, joy-filled exploration of capitals helps students learn the rules far better than they ever did when we did capitalization worksheets or I circled capitalization issues in papers, and no one feels judged for how they use capitals; on the contrary, they understand how the capitalization approach they already bring to texts and school exists in and interacts with the larger tapestry of human communication, and they learn how they can use capitalization to better express their voices.

Conclusion

One of the teachers I admire most, Dave Stuart Jr., has a sign at the front of his classroom that says Do hard things. One final trait the skunks share is that they are hard — and that is a good thing. Doing hard things is good for us in myriad ways, and the reward is very often worth the price of admission. When it comes to grammar and language, the reward for learning it is captured well in that first English grammar book by Robert Lowth in 1762. In it he defines grammar as “the Art of rightly expressing our thoughts by Words” (p. 1). While Lowth and I diverge in our approach to grammar in many ways, I could hardly think of a better definition.

Every human is born with an idiolect, or an individual dialect. This idiolect is a combination of grammar and usage rules, vocabulary, and pronunciations from their parents, caretakers, friends, and neighbors woven together into a beautiful, personal style. Each idiolect is singular; no one has ever communicated exactly like us or will communicate exactly like us again. This means we all have something to contribute, and I love grammar and language instruction because it can help our students to more rightly and more accurately express themselves and their unique voices and truths. I’ve also found that when grammar and language are taught in expansive, connected, and joyful ways, students see this too and the skunk slowly becomes de-scented and over time turns from a subject non grata to a welcomed guest.

References

Cordi, K. (2020, February 21). Teaching for joy [Conference session]. OCTELA 20/20: Envisioning Our Future(s), Columbus, OH, United States.

Engle, Randi A., Diane P. Lam, Xenia S. Meyer, & Sarah E. Nix. (2012), “How Does Expansive Framing Promote Transfer? Several Proposed Explanations and a Research Agenda for Investigating Them.” Educational Psychologist 47(3), 215-231.

Haussamen, B. (2003). Grammar alive! A guide for teachers. National Council of Teachers of English.

Lowth, R. (1762). A short introduction to English grammar: With critical notes. J. Hughs.

Newkirk, T. (2017). Embarrassment: And the emotional underlife of learning. Heinemann.

Stern, J., Ferraro, K., Duncan, K., & Aleo, T. (2021). Learning that transfers: Designing curriculum for a changing world. Corwin.

Weaver, C. (1996). Teaching Grammar in Context. Heinemann.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

The post Why Grammar Instruction Stinks, and How We Can Change That first appeared on Cult of Pedagogy. Three common issues contribute to grammar’s skunky status, but we can address these issues head-on and make it a favorite for our students and ourselves.

The post Why Grammar Instruction Stinks, and How We Can Change That first appeared on Cult of Pedagogy. Instruction, Podcast, English language arts Cult of Pedagogy